Rouault: Seeing Christ in the Darkness

IN THIS SHOW

IMAGE GALLERY

CALENDAR

IN THE NEWS

Seeing Christ in the Darkness: Georges Rouault as Graphic Artist

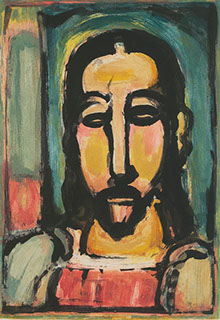

“Georges Rouault (1871-1958) was one of the few modern artists whose work was clearly religious,” says Bill Dyrness, Professor of Theology and Culture in Los Angeles. “But though he was a life-long Roman Catholic, his work was anything but Christian in the traditional sense. Too much of it seemed overly gloomy and depressing. Indeed for most of his life the Church resisted the darkness of his work—not until the end of his life did he receive a church commission. But the graphic art in this exhibition, done at the height of the artist’s powers, shows how deeply the artist identified with peoples’ sufferings and, indeed, saw within this darkness the salvation that Christ brought.

It is appropriate that the focus of this exhibit is on Rouault as printmaker, for it was especially in his graphic work that his religious vision took shape.

This show includes eighteen pieces from the Miserere series, five from Fleurs du Mal I, several colored pieces from The Passion and Fleurs du Mal III, along with two signed works and several other prints. Seeing Christ in the Darkness is an excellent collection of the world-class prints of one of the most important printmakers of the 20th century.

The exhibition's artwork includes

Miserere Series (19)

Plate 1 Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great loving-kindness

Plate 2 Jesus despised…

Plate 4 Take refuge in your heart, vagabond of misfortune

Plate 10 In the old district of Long Suffering

Plate 14 A young woman called joy

Plate 16 The upper class lady believes she holds a reserved seat in heaven

Plate 18 The condemned man has gone away

Plate 28 “He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live”

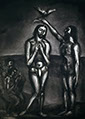

Plate 30 We…were baptized unto Jesus Christ, were baptized unto his death

Plate 31 “Love one another”

Plate 32 Lord, it is you, I know you

Plate 33 And Veronica, with her soft linen, still walks the road

Plate 35 Jesus will be in agony until the end of the world…

Plate 43 “We must die, we, and all that is ours.”

Plate 51 Far from the smile of Reims

Plate 54 Arise, you dead!

Plate 57 “Obedient unto death, even the death of the Cross”

Plate 58 “It is through his wounds that we are healed.”

Fleurs du Mal III (aquatint)

Golgotha, color aquatint

Face of Christ, color aquatint

Fleurs du Mal I (etchings)

Benediction

Christ Mocked

Satan II

Satan/Woman’s head

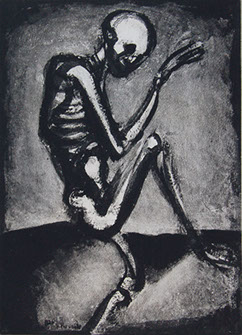

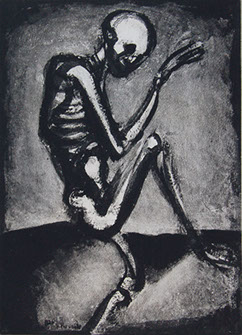

Skeleton

Passion (5)

Assistant Carrying the Cross, color aquatint

Christ et les Exegetes, color aquatint

Les Disciples, color aquatint

Christ au Faubourg, black and white aquatint

Christ au Faubourg, color aquatint

MISC (5)

Exude/Babylon, intaglio, cancelled plate

Resurrection, Intaglio, cancelled plate

Head of John the Baptist (signed)

The Christ on the Cross/Le Christ en Croix- lithograph

Petite Banlieue, lithograph (signed)

This show contains:

- An essay entitled, Seeing Christ in the Darkness: Rouault as Graphic Artist by Bill Dyrness who wrote Rouault: A Vision of Suffering and Salvation published by Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1971, a definitive work on the work and spiritual life of Georges Rouault.

- Brochure designed and ready for each venue to reproduce, either in color or in black and white.

- Digital file with all info needed for labels.

- Insurance will be supplied for the work in transit other than the $1000 deductible that will need to be covered by each venue.

- The show will be crated with instructions for shipping to the next venue.

Cost of rental is $750 per month (plus shipping). There is a two-month minimum. With the rental of two months the third month is free.

Miserere Series

Fleurs du Mal 1 and 111

Passion Series and Miscellaneous

Plate 1. Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great loving-kindness

Plate 2. Jesus despised…

Plate 4. Take refuge in your heart, vagabond of misfortune

Plate 10. In the old district of Long Suffering

Plate 14. A young woman called joy

Plate 16. The upper class lady believes she holds a reserved seat in heaven

Plate 18. The condemned man has gone away

Plate 28. He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live

Plate 30. We … were baptized unto Jesus Christ, were baptized unto his death

Plate 31. Love one another

Plate 32. Lord, it is you, I know you

Plate 33. And Veronica, with her soft linen, still walks the road

Plate 35. Jesus will be in agony until the end of the world…

Plate 43. We must die, we, and all that is ours.

Plate 51. Far from the smile of Reims

Plate 54. Arise, you dead!

Plate 57. Obedient unto death, even the death of the Cross

Plate 58. It is through his wounds that we are healed.

18 - 18

<

>

Benediction, Christ Mocked

Golgotha

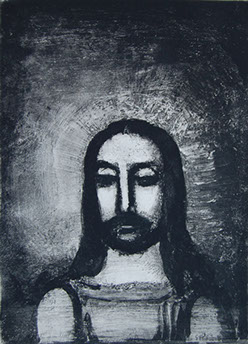

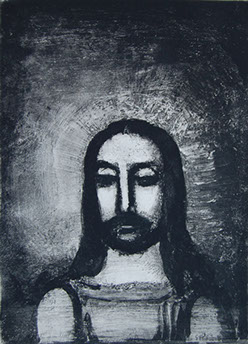

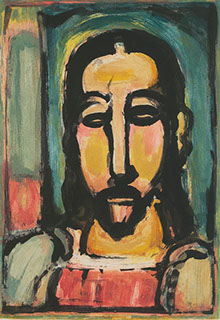

Face of Christ

Christ with Raised Arms

Satan

Skeleton

Satan/ Head of Woman

5 - 7

<

>

Assistant Carrying the Cross

Christ on the Cross, color aquatint

Conversation

Cross, engraving

Christ et les Exegetes,

color aquatint

Christ in the Doorway

Ecce Homo (Behold the Man)

Exude, Exodus, cancelled plate

Christ au Faubourg, black and white aquatint

Christ au Faubourg, color aquatint

Head of John the Baptist (signed)

Petite Banlieue (signed)

Resurrection, cancelled plate

Vase, Verve

3 - 14

<

>

Exhibitions of this Collection

January 1 to April 15, 2025

Belmont University

1900 Belmont Boulevard

Nashville, TN 37212

Contact: Dr. Todd Lake, todd.lake@belmont.edu

615 460 6628

October 14 – November 23, 2024

Concordia University Nebraska

800 N Columbia Ave, Seward NE 68434

Contact: James Bockelman, james.bockelman@cune.edu

January 1 to March 30, 2024

College of Central Florida, Webber Gallery

3001 S.W. College Road | Ocala, FL 34474-4415

Amanda Lyon | Gallery Coordinator

lyona@cf.edu

352-854-2322, ext. 1664 | Fax 352-873-5886

January 1 to April 30, 2023

St Georges Episcopal Church

4715 Harding Rd, Nashville, TN 37205

Contact person: Margery Kennelly Margery.kennelly@stgeorgesnashville.org

October 15, 2021 to April 30, 2022

Gordon Conwell Seminary

14542 Choate Circle, Charlotte, NC 28273

Contact: Wesley vander Lugt, wesley.vanderlugt@gmail.com

February 1 to August 31, 2021

St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

2128 Barton Hills Drive

Austin, TX 78704

Contact: Fr Zac Koons

zac@stmarksaustin.org

September 7 to December 7, 2020

Spring Arbor University

106 E Main St, Spring Arbor, MI 49283

Contact: Jonathan Rinck,

Jonathan.Rinck@arbor.edu

(800) 968-9103

The show rents for $750 /month, with a minimum of 4 weeks per venue. With the rental of two months the third month is free.

Bowden Collections offers a variety of traveling exhibitions available to museums, churches, colleges and seminaries: several feature the work of important historical artists such as Georges Rouault, Marc Chagall, Ottos Dix and Alfred Manessier; others explore topics related to the Bible. A packet containing everything needed to mount the exhibition with files for labels, itemized lists, a brochure or flyer in PDF format, high-resolution digital files of art in the exhibition, and shipping information is provided. Venues are responsible for the rental fee and shipping, usually to the following venue.

The quality of being Rouault is not something easy to love. His work is dissonant, dark, macabre, full of conflict. Critics have called it ugly, unpleasant, and tumultuous. Scholars debate whether he was an expressionist (he would have detested such a tag), a Fauve (plausible given his savage colorism), a neomedievalist (art should glorify God), or, with his focus on the subconscious, a surrealist (a very unsatisfactory label indeed). Undoubtedly, his technical and formal affinities lie with expressionism, but as Moreau counseled, he makes his own way. The idiosyncratic choice of imagery and themes found in Miserere et Guerre sometimes follows a logic that only Rouault could fathom.

For various reasons, Miserere et Guerre remained unpublished until 1948. As Stephen Schloesser has noted, this allows us to assess "the differences between contexts of production and contexts of reception." To these we might add a context of exhibition. Thirty-six of the images hung at Duke Chapel during Lent: Grouped in six sets of three along each side of the nave, these prints made for a bracing Lenten pilgrimage toward the altar. The gothic splendor of the chapel, with its deep shadows and soaring space, underscored the series' themes of darkness and hope.

Rouault appended his own captions, drawing primarily on the Bible as well as Pascal, Plautus, Lucan, Virgil, and Horace. He also canvassed some of his characteristic social themes: the abuse of power, bourgeois complacency, the plight of the poor and alienated, the evils of war. The variations in technique give these prints a kind of cadence, from the brushy "and Veronica with her delicate linen still goes her way" (plate 33), a tender evocation of the imprint of Christ's face on the saint's veil, to "In all things, tears" (27), an extensively reworked image in which a monumental, faltering figure is burdened by a strange knapsack. Is he a soldier, a refugee, or the Lord struggling on the road to Calvary?

The series title pages, Miserere ("Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving kindness") and Guerre ("They have ruined even the ruins"), have the appearance of gravestones or decorative emblems, the former elaborate and symbolic, the latter ordered and severe. Taken as a diptych, these two images ground the series in the dichotomies that Rouault returns to again and again: mercy/war, sacred/profane, seen/unseen, and Christ/man. Likewise, Rouault the mystic coexists with Rouault the ruthless chronicler of man's ridiculousness. The medieval sovereign with a rictus grin in "We think ourselves kings" holds court with a doleful clown in "Who does not paint himself a face." Satire pure and simple animates "We are insane," featuring two bourgeois men with rolling eyes, while in "Auguries" a woman is caught between two fortune-tellers.

The curatorial decisions about the chapel groupings are generally well considered, but at times one feels that Rouault's social conscience gains ascendance over his spirituality. For example, one grouping is described as emphasizing "the injustices of various power structures and the helplessness of its victims." These images—on one side "It is hard to live," "It would be so sweet to love," and "Jean-François never sings alleluia," and on the other, "The condemned man is led away," "His lawyer, in hollow phrases, proclaims his entire unawareness," and "Face to face"—do indeed depict corruption and the impossibility of earthly justice. But behind them is the ever-present idea of Christ, whose humiliation, and by extension our own, is not the end of the story.

At the nearby Nasher Museum, where the exhibition continues, the introductory wall text describes these 19 works on view as representing "the plight of the suffering refugee, the devastation of the land, and the cruelty and corruption of the powerful." Much of Rouault's work in the early 20th century was influenced by his own experiences of poverty and his participation in the Catholic activist movement. But to reduce his work to concerns for immigrants and the environment is to overlook the central fact of his artistic motivation: that man's tragic fate can only be reconciled by coming to terms with Christ on the cross.

In fact, being a Catholic in France in the early 20th century called for a particularly tenacious and robust form of faith. In 1901, as part of a larger move to separate church and state, the French passed a law making religious communities illegal. The Roman Catholic resurgence of the late 19th century were cut short by the Great War and the socialist forces taking root in Europe. "As a Christian in such hazardous times," Rouault wrote, "I believe only in Jesus on the cross. I am a Christian of olden times." His words show his instinctual unity with believers throughout the ages and an essential humility and moral strength that require no cultural prevarication.

As works of art, these images are fierce and marvelous, remarkable for their line, depth, and lambent tonalities. Their resplendence lies in the artist's unshakable faith and his equanimity about man's plight, continually offering pity rather than denunciation, hope in place of despair. How does he achieve this? As he wrote in the series preface, "Jesus on the cross will tell you better than I."

Leann Davis Alspaugh is managing editor of the Hedgehog Review.

® 2025 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED | design by www.isleydesign.com